It’s well known that teachers faced many challenges during the pandemic, but those new challenges often just piled on top of existing duties and magnified the persistent and growing number of responsibilities placed on teachers across the country. This reality has not gone away despite the dissipating urgency of the pandemic, as “the roles of schools and teachers have grown over time,” according to The 74M. In fact, the article notes that 87 percent of teachers agree they have too many responsibilities to be effective educators, citing the 2023 Voices from the Classroom survey. What else did teachers elevate? The Rodel team surfaced a few key areas to explore. Collaboration “First and foremost, [collaboration] means easing some of these growing pressures and responsibilities and increasing the amount of time in the day dedicated to teachers’ core responsibilities.” Teachers are often asked to take on more roles in their schools on top of their teaching responsibilities, and many times, without additional compensation. We also know this is particularly true for teachers of color, who are often asked to take on additional responsibilities, serve on committees, or be default leaders without additional pay, compensation, or recognition. Compensation “Next, teachers must be paid the compensation they deserve.” Teacher compensation has been an ongoing issue across the country for years. Educators are paid wages that ignore their expertise, working conditions, and the impact they have on students every day. Compensation has not kept pace with the role of teachers as they continue to get more added to their plate every school year. Not only has it not kept pace with the evolution of the teaching role, but the gap in pay between educators and their college-educated peers continues to grow. The Economic Policy Institute reported that in 2021, teachers earned 23.5 percent less than their fellow college-educated peers in other industries. Educators deserve to receive compensation that reflects their expertise, workload, and the incredible impact they have on students every day. Teachers need time for their own support/processing “It is important to acknowledge the importance of supporting the mental health of not just students, but educators.” “Providing mentorship and peer-to-peer growth opportunities and involving teachers in school and district decision making are concrete ways to not only bolster their well-being, but also bolster their effectiveness.” Education, more so than many other professions, can be extremely stressful. A recent RAND Corp. study found that teachers are nearly twice as likely as other working adults to report having difficulty coping with job-related stress, and 10 percentage points more likely to experience burnout. Beyond academic growth and attainment, educators are often asked to monitor their student’s well-being, including mental health. Still, few people know the amount that goes into being an educator and that their mental health can be compromised in such a challenging career. Educators benefit from time to process what is happening in their classrooms and having time to connect with their peers through mentorship or the sharing of opportunities to get involved in their districts. What is Rodel Doing to Support? Affinity Groups Nationally, we are facing a teacher shortage and Delaware has not been spared from this growing issue. Some of these issues can be attributed to the number of responsibilities that teachers have on their plates. And for teachers of color, this is exacerbated by the unique challenges they face because of their race. In addition to cultivating our next generation of leaders by teaching and supporting students, teachers of color face micro- and macroaggressions daily, making this work much more difficult. For anyone close to education or educators, it is not surprising to hear that educators are feeling burnt out and unsupported. One way that some districts in Delaware are supporting their educators is by implementing racial affinity groups. Work from The Black Teacher Project and Education Trust has shown that racial affinity groups can increase retention of teachers while also providing mentorship, affirming identity, and cultivating supportive relationships. Red Clay and Colonial school districts decided to pilot affinity groups in the spring of 2023 to create spaces for their educators of color and allies to talk and learn together. Rodel has supported the implementation by assisting with training and project management of this exciting opportunity. Racial affinity groups are not new; they are well known in corporate spaces and are growing in popularity for educators as well. In the pilot groups, our partner districts interviewed and selected affinity group leaders who were interested in creating brave spaces for their colleagues to either unpack the tough times they had within the school or create space for non-BIPOC educators to learn how to be strong and supportive allies. These spaces are unique because both Red Clay and Colonial intend to use feedback from these groups to understand issues within the district and take action to create an inclusive and supportive community that will encourage educators to stay in the classroom and stay with their respective districts. Teacher Leadership/Compensation To honor and respect the expertise of teachers, we must think innovatively about what teacher leadership is and how it is recognized both informally in schools and formally through compensation. Luckily, Delaware is beginning to dedicate resources to exploring this topic. In collaboration with the Delaware Department of Education (DDOE), Rodel is creating a teacher leadership committee, comprised of teachers working across the state. Their charge is to create an innovative teacher leadership model that is culturally responsive, as well as teacher and student-centered. The committee will be established later this fall and will look to national and local expertise of teachers and teacher leaders to create a blueprint for teacher leadership in Delaware, which will include: a working definition and job description, recommended teacher leadership staffing models, and a rubric for identifying culturally proficient and equity-centered teacher leaders. As part of Senate Bill 100, a subcommittee dedicated to exploring compensation for teacher leadership has formed under Delaware’s Public Education Compensation Committee (PECC). As members of the Rodel Teacher Network’s work group recommended, it is important to appropriately and respectfully compensate teacher leadership roles, while balancing the local needs of Delaware school districts. Through fair and appropriate compensation for the varied teacher leadership roles in schools, we begin to honor the expertise and impact teacher leaders have in schools every day.

-Key themes from the survey include the need for collaboration, compensation, and time.

-Rodel and partners are working on several fronts in Delaware, from racial affinity groups to teacher leadership.

Burnout Remains a Reality for Many Educators. What Support is On the Way?

Building Self-Identity and Mapping the Future: How Delaware is Beginning to Rethink Middle School

National leaders like Advance CTE are helping lay the groundwork for middle grades redesign. Having been cited and celebrated as a national leader in career pathways, Delaware has built a robust career and technical education (CTE) system that is integral to high school in Delaware. Despite the state’s success, it has become increasingly clear that starting earlier with career exploration, experiential learning, and positive identity development, from an equity lens, are the next major areas of focus. As partners in the work reflect on, expand, and reshape career and technical education, new initiatives have kicked off to both address blind spots of the past and create innovative programming for the future. One of the big shifts comes with building equitable programming as early as fifth grade that fosters student self-and occupational identity. This project, known as Rethinking Middle Grades, focuses on creating strong supports and programming for middle-grade students to meaningfully connect exploration, learning, and a positive self-image to occupations and their community. Students enter eighth grade knowing that high school is right around the corner. With the work of this project, new CTE standards for middle grades, counseling models, and connection between in- and out-of-school experiences would allow that student to at least begin thinking about the road ahead. Such supports would help to increase career awareness and exposure, increase self-awareness and potential occupational identity, and develop both foundational and employability skills—before students enter high school, where they are expected to select a career “pathway” or area of study. What’s Happening in Delaware? “Rethinking Middle Grades” is still in its early stages, and these concepts won’t be classroom-ready in Delaware for at least a few more years. For now, the group is working to build equitable and well-rounded CTE programming in middle grades (typically grades five through eight) that cultivates student identity through youth-centered career exploration. This work, led by a steering committee of diverse partners in communities, schools, industries, and organizations across Delaware, looks to foster and celebrate a young person’s identity, assets, and aspirations as they build an in-depth understanding of their in- and out-of-school communities, the working world and their place in these spaces. To be clear, this group is not building the rigorous career pathways that today enroll thousands of Delaware high school upperclassmen. Instead, the goal is to set students up for success prior to entering high school, for it is important that every student enters high school having found success in career education, academic, and social-emotional programming in middle grades that inspires their identity and a path to postsecondary success. Why It’s Not “Middle School Pathways” And Other Answers We Know Now Why middle grades? The expansion of pathways in high school over the past few years showed that many students arrive in ninth grade without a positive and healthy self-image and sense of place as it relates to their school, community, and their future occupation. These gaps are usually caused by inconsistent access to resources, an unequal playing field, and low expectations often applied to middle school-aged youth. Does this mean Delaware pathways programs will be available in middle school? Content-specific pathway programs will remain a core part of the high school experience. The middle grades project allows students to have a stronger understanding of their options and be well-equipped to make decisions on pathways and early postsecondary opportunities that best suit their interests, goals, and identity in high school. By providing structures, intentional programming, and training, this design project will eventually give students the tools and supports they need for self and career exploration. Does this shift in programming lock students into a specific pathway? Since students will be engaged in exploration opportunities, it does not lock students into a specific pathway. Instead, it provides them with the opportunity, supports, and tools to explore their interests and the potential pathways, occupations, and opportunities that connect to those interests. Aren’t middle school students too young to know what career path they want to explore? Every student is different. Some students may know what careers interest them at a young age while others may need time trying different careers. Regardless, it is never too early to name one’s assets and interests. Educators are charged with listening to their students and learning about their passions and gifts. Young people should have access to coaches who offer inquiry and resources that connect them to an evolving vision of their future in work and in the community. What about students who want to go to college or the military? This shift in middle school programming is for all students. All students benefit from exploring their interests and developing a positive and healthy self-image as it relates to their school, community, and future occupational identity. In order for high school to be a launching place for young people to accomplish their postsecondary goals (whether it is to attend college, enter the workforce, etc.), middle grades must provide programming that fosters exploration of interests and makes intentional connections to career and postsecondary paths that young people can see, plan for, and actualize. What will this tangibly look like in middle schools? We aren’t certain what the final product will actually look like when all three phases of the design process are complete. We know that coming out of each phase will be a framework that will drive change in middle grades. For example, the first phase of work is the creation of CTE standards in middle grades. These standards will be drafted this summer and will be up for public review and feedback this fall. The final product of this phase will be standards for middle grades teachers and counselors and a related profile of a high school-ready student to guide and drive career exploration and identity development in middle grades.

-A local committee is in the early stages of a project known as Rethinking Middle Grades—focused on creating supports and programming for students that connects learning and self-image.

-Part of the Delaware Pathways initiative, this programming will middle schoolers build bridges to high school and help them identify areas of interests as they select schools and pathways.

How Will Delaware Schools Spend Federal Stimulus Funds? A Breakdown

– Delaware received $411 million for K-12 education as part of President Joe Biden’s $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act.

-Local schools and districts submitted formal plans detailing how they will use these funds.

-Some key themes have emerged from those plans, including: addressing learning loss, educational technology, mental health services, and serving low-income families, children with disabilities, English learners, racial and ethnic minorities, and more.

President Joe Biden’s $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act, the third federal stimulus package since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, provides $350 billion for states, local governments, territories and tribal governments, with around $125 billion nationally earmarked for K-12 schools through the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funding stream.

Out of the $125 billion dollars in the ESSER III pot, Delaware received approximately $411 million. As written in the federal law, 10 percent of Delaware’s funding went to the state Department of Education (DDOE), and the remaining 90 percent went directly to Local Education Agencies (LEAs), otherwise known as districts and charter schools.

In order to receive the full amount of funding under ESSER III, both the DDOE and LEAs are required to submit plans detailing how they will use these funds (which in turn were required to be posted publicly). DDOE’s plan was submitted in June and recently approved by the U.S. Department of Education.

As of this week, all of the district and charter school plans have been posted on DDOE’s website.

We looked at all of the 42 plans to understand how LEAs in Delaware plan to use their funding.

Update (2/16/22): Check out this latest analysis from FutureEd @ Georgetown University, which breaks down local spending by district poverty level, among many other revealing highlights.

Guidelines for LEAs

- Funding was distributed to LEAs based on Title I.

- LEAs were required to use 20 percent of their funding to address the academic impact of learning loss on their students. All plans meet and, in some cases, exceed that minimum. Other than that, the guidelines were focused on the impact of the pandemic on students and schools.

- As outlined in the state’s ESSER plan, at a minimum, LEA plans had to describe the following:

- How funds will be used to implement COVID-19 prevention and mitigation strategies

- How LEAs will use the mandatory set-aside for learning loss and other allowable uses

- How the LEA will ensure that the ESSER funded interventions will respond to the needs of all students, and particularly students disproportionately impacted by COVID-19

- The plans vary, with some providing detailed information for each initiative and use of funding and other plans offering general or minimal detail.

- The plans are district-level and charter school-level—there are no individual school-based plans within districts available on the Delaware Department of Education’s website.

Learning Loss, Technology, Lead Areas of Focus

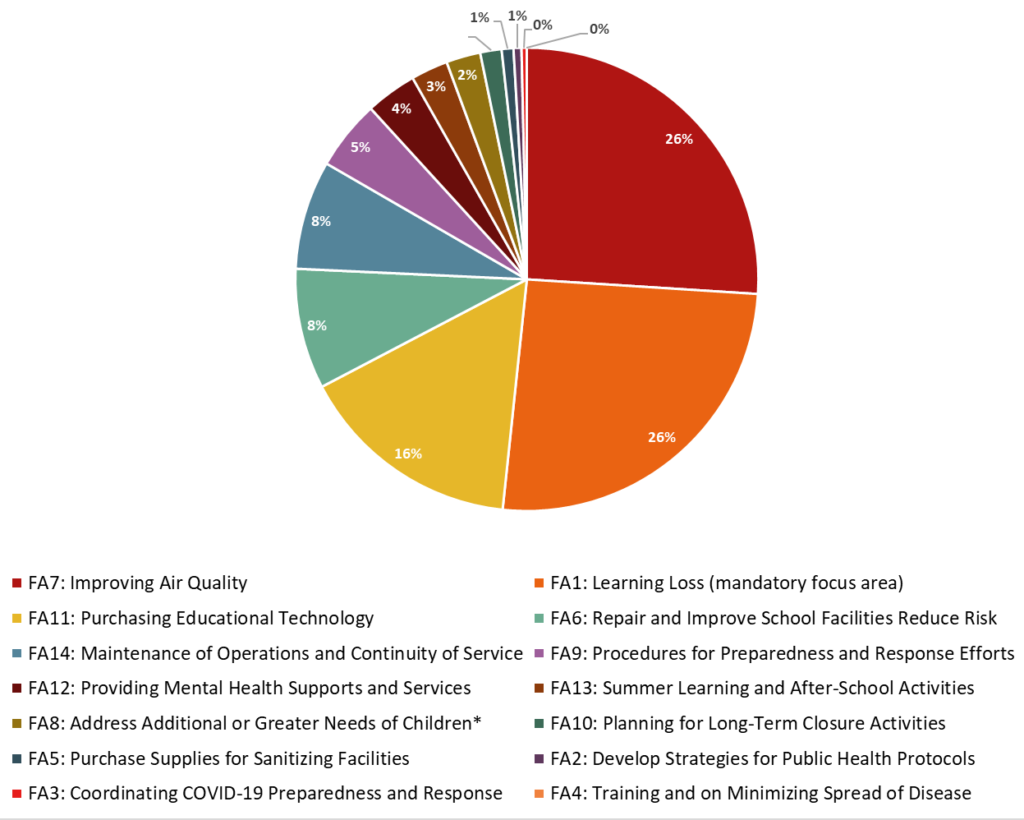

Districts and charters had to identify on which areas out of 14 provided in the grant they plan to focus their portion of ESSER III funds. Out of the 14 areas, the five most commonly identified include:

- Addressing Learning Loss

- Purchasing Educational Technology

- Providing Mental Health Services and Supports

- Other Activities for Maintenance of Operations and Continuity of Service

- Supports for Students with Additional and/or Greater Needs

*This includes children from low-income families, children with disabilities, English learners, racial and ethnic minorities, students experiencing homelessness, and foster care youth. **Percent is out of the total number of LEAs (which is 42) Source: Delaware Department of Education (2021). District, charter spending plans. Retrieved from: https://www.doe.k12.de.us/Page/4458 When looking at the money allocated to the focus areas identified by districts only, repairing facilities and improving air quality emerges as a major theme—and a major price tag. While more districts identified purchasing education technology over improving air quality as a focus area, improving area quality carries a much higher allotment of money. *This includes children from low-income families, children with disabilities, English learners, racial and ethnic minorities, students experiencing homelessness, and foster care youth. Note: This chart does not include charter school focus areas or allocations. Some districts included portions of their ESSER II funding in their budget allocations in their ESSER III plans. Source: Delaware Department of Education (2021). District, charter spending plans. Retrieved from: https://www.doe.k12.de.us/Page/4458 Further, the chart below shows the approximate percentage breakdown of where districts are allocating their ESSER III money by focus area. As shown below, a little over three quarters of the funding is allocated to the following areas: *This includes children from low-income families, children with disabilities, English learners, racial and ethnic minorities, students experiencing homelessness, and foster care youth. Note: This chart does not include charter school focus areas or allocations. Some districts included portions of their ESSER II funding in their budget allocations in their ESSER III plans. Source: Delaware Department of Education (2021). District, charter spending plans. Retrieved from: https://www.doe.k12.de.us/Page/4458 Hiring Staff, Mental Health, and Extra Learning Opportunities, A Major Focus LEAs were also required to answer more targeted questions about the general plan and use of ESSER III funds. Combined with the focus areas, six areas were most commonly identified. Trends across all districts and charters are clear within this required bucket of spending. Many schools are relying on evidence-based practices for accelerated learning to address learning loss brought on by the pandemic. All schools mentioned versions of the following: Overwhelmingly, schools are using additional ESSER III funds for technology. Many LEAs pointed to the importance of a 1:1 device-to-student ratio but others included training for educators, hiring a technology consultant or supervisor, licenses for digital learning tools, and updating infrastructures such as broadband and Wi-Fi. The majority of plans (around 30) mentioned hiring new staff for positions like interventionists, counselors, psychologists, special education teachers, paraprofessionals, and others. Plans also mentioned addressing substitute needs, transportation needs, and indirect costs. Others pointed to utilizing screeners for mental health and socioemotional needs, working to provide workshops and enhance communication with families, and partnering with outside organizations. Stay tuned to the Rodel blog for more updates as they come.

Focus Area (FA)

Approximate Number of LEAs

Percent**

FA1: Learning Loss (mandatory focus area)

42

100%

FA11: Purchasing Educational Technology

29

69%

FA14: Maintenance of Operations and Continuity of Service

27

64%

FA12: Providing Mental Health Supports and Services

24

57%

FA8: Address Additional or Greater Needs of Children*

22

52%

FA13: Summer Learning and After-School Activities

20

48%

FA6: Repair and Improve School Facilities Reduce Risk

19

45%

FA7: Improving Air Quality

19

45%

FA5: Purchase Supplies for Sanitizing Facilities

15

36%

FA2: Develop Strategies for Public Health Protocols

10

24%

FA10: Planning for Long-Term Closure Activities

8

19%

FA3: Coordinating COVID-19 Preparedness and Response

7

17%

FA9: Procedures for Preparedness and Response Efforts

6

14%

FA4: Training and on Minimizing Spread of Disease

1

2%

Note: “LEAs” include districts and charter schools. Numbers are approximate based on analysis of plans.

Focus Area

Range

Approximate Number of Districts That

Prioritized This

Focus Area

FA1: Learning Loss (mandatory focus area)

$75M-100M

19

FA7: Improving Air Quality

$75M-100M

14

FA11: Purchasing Educational Technology

$50M-75M

16

FA14: Maintenance of Operations and Continuity of Service

$25M-50M

15

FA6: Repair and Improve School Facilities Reduce Risk

$25M-50M

13

FA8: Address Additional or Greater Needs of Children*

$1M-25M

12

FA12: Providing Mental Health Supports and Services

$1M-25M

12

FA13: Summer Learning and After-School Activities

$1M-25M

12

FA5: Purchase Supplies for Sanitizing Facilities

$1M-25M

11

FA2: Develop Strategies for Public Health Protocols

$1M-25M

6

FA10: Planning for Long-Term Closure Activities

$1M-25M

6

FA3: Coordinating COVID-19 Preparedness and Response

$1M-25M

5

FA9: Procedures for Preparedness and Response Efforts

$1M-25M

4

FA4: Training and on Minimizing Spread of Disease

$1M-25M

1

Providers, Families, Business Community Agree: Delaware’s Child Care Crisis Imperils More than Just Parents

– Delaware’s child care crisis has far-reaching effects, from the household to the local business community, according to recent survey data.

– Employers cite lack of child care for stalled workforce and recruitment efforts.

– 96 percent of child care centers in Delaware are experiencing a staffing shortage, leaving families to face long waitlists.

For Delaware parents with young kids like Rodel’s own Kim Lopez, the state’s child care crisis is a daily reality.

But today, the crisis has spilled beyond just households with kids and their would-be child care centers.

The ripple effects into businesses, the general workforce, and the overall economy are resonating clearly. Three recent surveys provided insights into how three cross-sections of society are grappling with child care challenges as the pandemic lingers on.

Impact on Delaware Businesses

As evident during the pandemic, the lack of available (or affordable) child care has a massive effect on the economy and workforce participation. A report by ReadyNation found that nationally, lack of child care was the third-most-reported reason for unemployment in December 2020. A year after lockdown the same report found that approximately 15 percent of women ages 25 to 44 were not working due to problems with child care. Employers (around 30 percent) also stated that employees cite child care issues as a reason for employment changes.

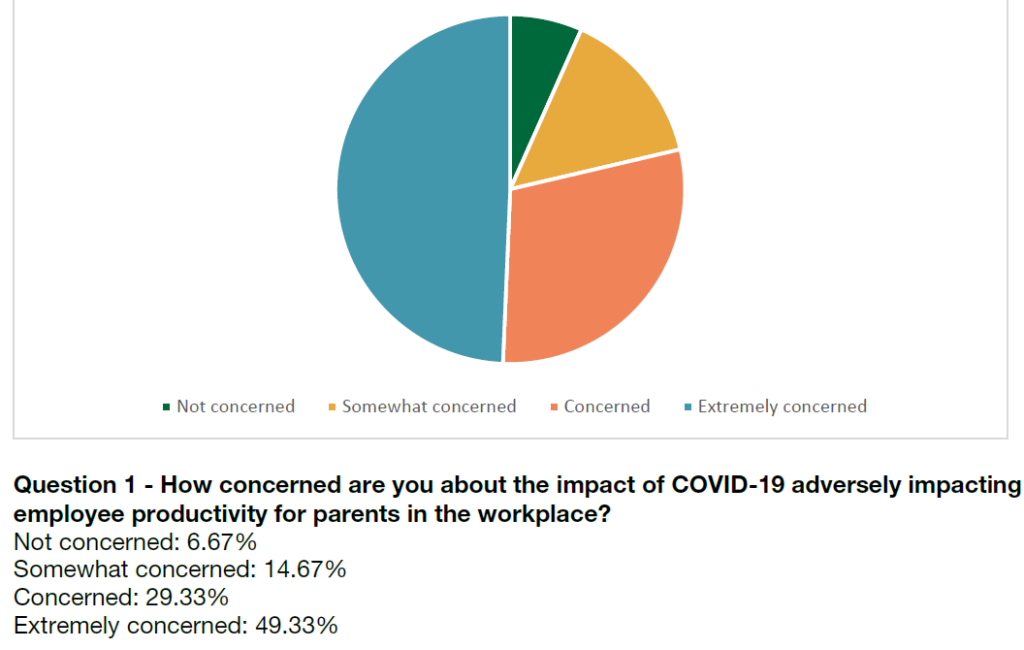

Employers in Delaware are sharing their concerns about child care impacting their workforce and recruitment efforts. In an initial survey of Delaware employers, led by the Delaware State Chamber of Commerce and the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia:

- 78 percent are concerned or extremely concerned about the impact of COVID-19 adversely impacting employee productivity for parents in the workplace

- 72 percent have found it difficult, very difficult, or extremely difficult to recruit/retain employees because of the impact COVID-19 has had on child care and school schedules

Their concerns about employees include: high cost of care, availability of care, and lower productivity. Click here to see more results.

“The bulk of our daily absenteeism is for child care,” said one survey respondent. “With schools not fully operational and child care at an all-time low, it is difficult to get child care.”

The DSCC has included child care as essential in its Road to Recovery plan, recognizing the importance of child care for employer recruitment and retention.

[Read: The Economics of Child Care from Delaware Business magazine]Impact on Providers and the Child Care Workforce

Like most industries, the pandemic exasperated the early childhood staffing challenge. A recent national survey on child care programs and the pandemic showed that 96 percent of child care centers in Delaware are experiencing a staffing shortage (with many serving fewer children). Many have had to reduce their operating hours in order to cope with the shortage while others have had to close classrooms. Some providers that have capacity do not necessarily have the ability to enroll up to capacity due to the workforce shortage, leaving families to face indefinite waitlists.

When looking at recruitment challenges, 73 percent of survey respondents identify wages as the biggest factor because potential applicants are recognizing they can make more money working elsewhere. Similarly, 57 percent of respondents said that low wages are the most common reason that educators leave the field.

The crisis in the field has left 46 percent of respondents to consider leaving their program or closing their family child care within the next year.

While Delaware has relied on federal stimulus dollars to support centers and families, these new funds address the new problems brought on by the pandemic meaning, the old problems that plagued the child care industry before, are still very much present and further exasperated by the new challenges of COVID.

Higher costs associated with pandemic safety protocols, decreased enrollment, and lower revenue forced many child care centers nationwide and in Delaware to shut down classrooms or close their doors entirely. These new challenges have built on the financial predicaments early child care centers faced before the pandemic.

Impact on Children and Families

Almost half of all children ages three to four were not enrolled in an educational setting before kindergarten. While the issue is complex, there are two main reasons for the lack of enrollment: supply and affordability of quality child care.

In Delaware, there is an insufficient supply of options by location, age groups served, and hours of service. For example, 47 percent of the state’s birth through age five population live in Sussex and Kent counties. But those counties only contain 38 percent of the state’s early learning programs. Only 77 percent of programs accept infants under one year old, and only three percent of centers offer extended hours.

Child care is also expensive for families across income levels, pandemic or not. In Delaware, child care for one child costs approximately 20 percent of a median family income, or $13,000 per year, per child. Prior to the pandemic, the cost of child care led to half of Delawarean parents/guardians to not grow the economy – meaning they weren’t going back to school, working, having another child, or buying a house.

Higher costs associated with pandemic safety protocols, decreased enrollment, and lower revenue forced many child care centers nationwide and in Delaware to close their doors. While some child care facilities have reopened, many have multiple classrooms still closed.

According to the Delaware Readiness Teams survey from this summer, families continue to struggle finding care. While a majority of respondents indicated that they wanted their children to return to an educational setting, almost 40 percent of survey respondents indicated that their child(ren) was at home with a parent or other caregiver. Before the pandemic, about 40 percent of respondents indicated that they used full-time child care. However, during the crisis, that percentage dropped to 34 percent.

It’s not surprising then that more than half of families (60 percent) remain concerned about balancing family and work demands with caring for their child(ren).

Delawareans are speaking up. Click here to join advocates in urging lawmakers to increase child care investments