Updated on April 14, 2021 – Click here to see a charter- and district-level breakdown of stimulus dollars.

Along with the passage of the $1.9 trillion federal stimulus package that President Joe Biden signed into law last Thursday comes huge implications for the education world. While $1,400 stimulus checks (headed to around 446,105 Delaware households, according to Sen. Tom Carper) may generate the most buzz this week, we shouldn’t lose sight of what the stimulus means to our local school community.

The package will provide $350 billion for states, local governments, territories and tribal governments, with around $123 billion earmarked for K-12 schools. The legislation also includes funding for colleges and universities, transit agencies, housing aid, child care providers and food assistance.

| March 2020 (Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund) | December 2020 (Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act) | March 2021 (American Rescue Plan Act) | |

| National K-12 Allocation | $13 billion | $54 billion | $123 billion |

| Delaware K-12 Allocation | $43 million | $183 million | $411 million |

The bill, known as the American Rescue Plan Act, marks an enormous uptick in K-12 funding, almost 10 times the amount included in the original stimulus. In addition to the previous two stimulus packages under the federal CARES Act in 2020, which included infusions of $13 billion last March, and another $54 billion in December, this plan has the opportunity to serve as a critical lifeline for students, educators, and families.

How Much Will Delaware Receive?

Funding for Elementary and Secondary Schools

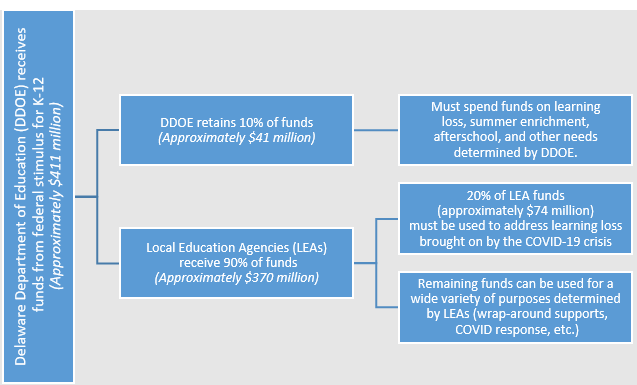

Of the approximate $123 billion K-12 pot, Delaware is estimated to receive around $411 million. The majority of the funding, around $370 million, will go directly to local education agencies (LEAs), e.g. local districts and charter schools. Twenty percent of the funding LEAs receive must be allocated to addressing student learning loss brought about by the pandemic. The remaining 80 percent of funds LEAs receive can be spent on a wide variety of items, such as activities and programs to address the unique needs of high-need students, materials and supplies related to COVID response, educational technology, facility maintenance, and wrap-around supports for students’ mental health and social and emotional learning.

After dispersing the majority of funds (90 percent) directly to LEAs, The Delaware Department of Education must set aside the remaining dollars, which totals around $41 million. Those dollars must be allocated according to certain parameters, including addressing learning loss (five percent), summer enrichment (one percent), and other educational needs.

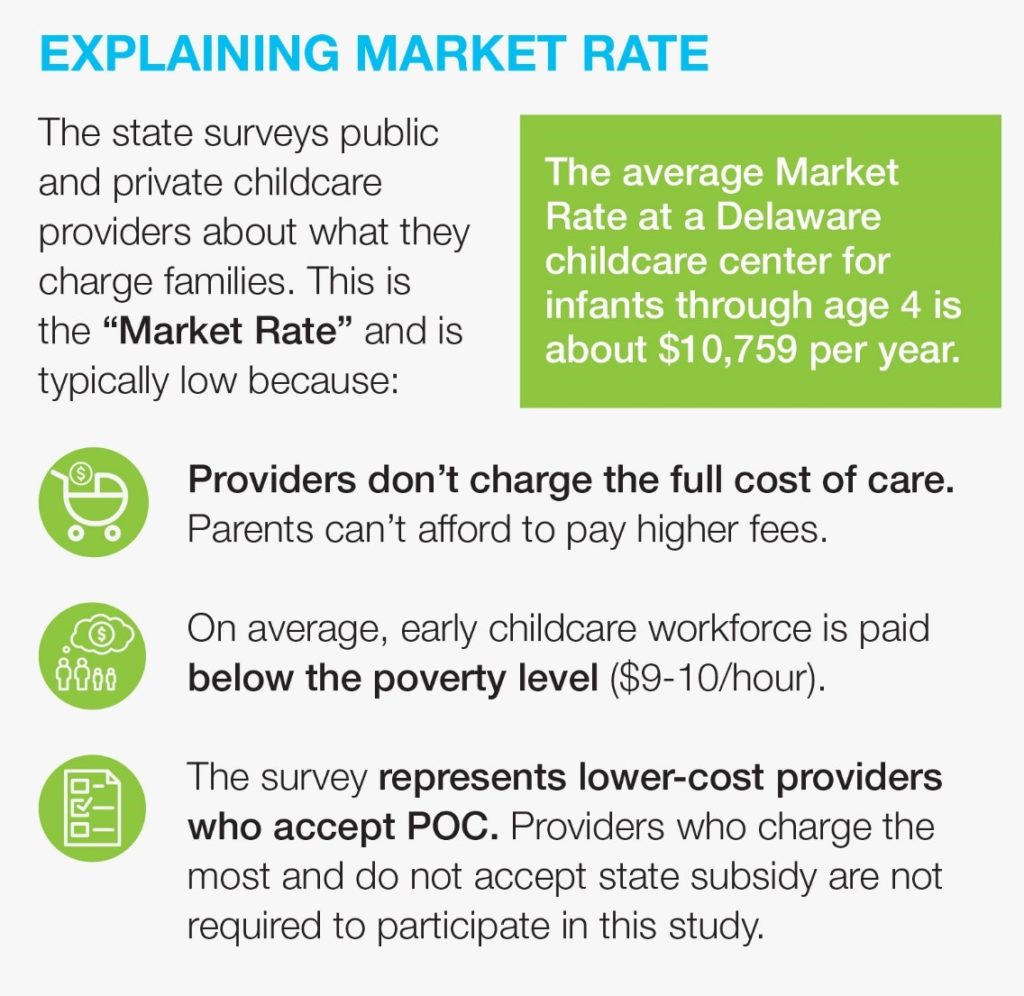

Early Child Care Crisis

Thanks to passage of the American Rescue Plan Act, the nation’s child care sector will receive around $39 billion in direct relief funding. Delaware’s child care industry should receive around $109 million of that. The funding is broken into two streams: one—$42 million—will provide expanded child care assistance (via the Child Care and Development Block Grant) to families and providers, including supporting the child care needs of essential workers. The remaining $67 million stream creates a stabilization fund for eligible child care providers, many of whom are struggling to keep their doors open.

The new stimulus also provides $1 billion in emergency funding for Head Start in order to help maintain access and services for children and their families. Delaware is estimated to receive almost $2.5 million from this for Head Start in addition to what the child care industry is expected to receive.

Other Things to Watch

- The bill also includes statements on the maintenance of equity of education funds. These statements serve as guardrails to try to prevent or minimize state and local funding cuts to high-need and high-poverty schools.

- While LEAs can utilize some of their funds for education technology, the bill allocates an additional $7 billion for an Emergency Connectivity Fund to support access to devices, internet, and connectivity for schools and students.

- The American Rescue Plan provides around $40 billion for the higher education emergency relief fund. Delaware is estimated to receive around $100 million from this pot of funds for higher education.

State, county, and local governments will also get a huge chunk of relief funding. Projections see Delaware receiving around $1.4 billion total, with further breakdowns at the state and local governments looking like this:

| State Government | $913 million |

| City of Wilmington | $55.26 million |

| City of Dover | $6.9 million |

| New Castle County | $108 million |

| Kent County | $35 million |

| Sussex County | $45 million |

Those dollars could have ripples into the education space. Some of it is earmarked for housing assistance, infrastructure, capital projects, small business and nonprofit supports, and more.

For now, state officials will gather intel and guidance on how to utilize the funds. We’ll keep you updated.

Additional Resources: