“Falling Enrollment” Original painting and banner art by Madison Plazio, McKean High School

For the first time in a decade, Delaware public school enrollment has dropped. This trend spans the country—just one of the many shakeups caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. In Delaware, enrollment triggers a handful of important policy and budgetary questions. A drop in public school enrollment brings many concerns with it, such as: a potential decrease in school funding, early learners starting behind when it matters most, and missing students who haven’t received a formal education since schools shutdown in March 2020.

Delaware’s Numbers

According to data released from the Delaware Department of Education (DDOE), enrollment dipped by more than 2,400 students, a 1.7-percent decrease from last year. All but four districts saw a decrease in total enrollment for this school year. Public charter schools, however, saw an increase in student enrollment with an additional 544 students, or a 3.3-percent increase from the previous school year.

Meanwhile, enrollment in non-public schools showed staggering increases, according to DDOE. COVID-19 inspired the emergence of learning “pods,” or multi-family homeschool set-ups, as well as other homeschool options. This increase in enrollment comes after nearly a decade of decreasing non-public school enrollment. An additional 2,439 Delaware students attended non-public schools this year compared to last year (a 16-percent increase).

- 4,512 Delaware students are now enrolled in single-family homeschools, an increase of 1,742 students (a shocking 63-percent increase) from 2019.

- 402 Delaware students enrolled in multi-family homeschools, which represents a whopping 49-percent increase as enrollment grew from 269 students since last school year.

- Private schools also saw an increase in enrollment with an additional 564 Delaware students, or a 4.4-percent increase, bringing total private school enrollment to 13,256.

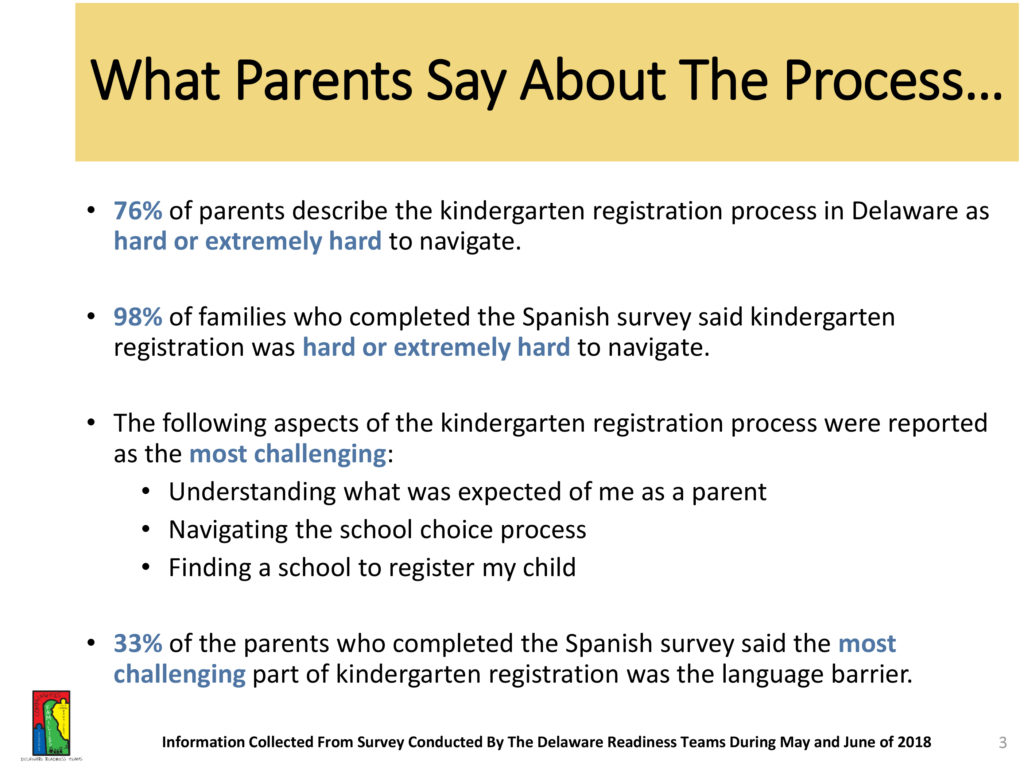

The drop in public-school enrollment seems to be most drastic in the early years, specifically kindergarten and pre-K. Enrollment of three- and four-year-olds in district-based preschool programs dropped by over 200 students, or 10 percent compared to last year. It’s the first decrease in the past five years, bringing the state’s total enrollment almost back to where it was in 2019.

Non-public schools have seen the reverse effect. When compared to all other grades, kindergarten has the largest number of Delaware students attending non-public school this year, with a total of 1,712 students. Out of all grades, kindergarteners also made up the largest group of Delaware students who attend single-family homeschools and private schools this school year.

The public system also lost a notable number of high school seniors. During the December State Board of Education meeting, Secretary Bunting noted a drop in public school enrollment of the class of 2021 citing potential reasons such as students assuming jobs to help meet the economic challenges of their families brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.

National Context

So far, there has been no national data released on the overall impact COVID-19 wrought on public school enrollment. Chalkbeat released information from a survey of 33 states’ preliminary enrollment numbers and the results are grim. Across the states surveyed, public school enrollment has dropped by 500,000 students, a two-percent decrease nationwide.

Like Delaware, many states across the country have and continue to report on the widespread decrease in public school enrollment for the current school year. Some examples of this are Massachusetts where public school enrollment dropped by nearly four-percent (37,000 students) and Arizona where enrollment is an estimated 50,000 students less since last year, a five-percent drop. Also similar to Delaware, states across the country have experienced the sharpest drop in early years. States like Washington experienced steep decreases in kindergarten enrollment with a 14-percent drop from the previous school year.

Implications and Considerations

- Reasons to explain the drop vary. Some states, like Delaware, have reported an increase in private and parochial school enrollment, suggesting that many families have turned to non-public schools to educate their children this year. A report from Bellwether Education suggests potential reasons for a decrease in public school enrollment could be: non-mandatory kindergarten in some states (not the case in Delaware), parent perception of remote learning, families having alternatives available for childcare, or families feel they can meet their child(ren)’s needs on their own.

Many families and students have struggled to enroll, engage, or connect with any formal education this year due to the barriers and crises the pandemic has created and amplified for students, such as: housing insecurity, mental health crises, internet access, technology access, and economic hardship. Anecdotally, teachers say decreased enrollment of some teenage students has been driven by economic, childcare, or other demands of the students in their household caused by the pandemic.

- A worrying drop in kindergarten could mean students start further behind since research shows early learning is critical to a child’s foundational skills and educational success. The most concerning is kindergarten children who are not enrolled in public school or any other educational setting this year (private, home school, etc.). Not attending some form of school this year could lead to unmet academic and social-emotional learning needs. It could also prevent or delay the delivery of early intervention services to children and limit access to health and nutrition services typically provided at school.

- These numbers reflect students enrolled in public school—but what about students who aren’t? Many families turned to non-public options like private and home schools this year to educate their children, but what about students who are not enrolled at all? The term “missing students” has been used across the nation to refer to students who are completely unaccounted for. A Bellwether Education report suggests that there could be up to three million marginalized students nationwide who are not enrolled anywhere—in public or non-public school. Schools and districts across Delaware and the U.S. have worked to reach students and ensure they are connected and engaged. Despite efforts—students are still missing, and it’s unclear where the students who are completely unaccounted for actually are. It’s also unclear if these students, and students who transferred to a non-public school this year, will return to public schools next school year.

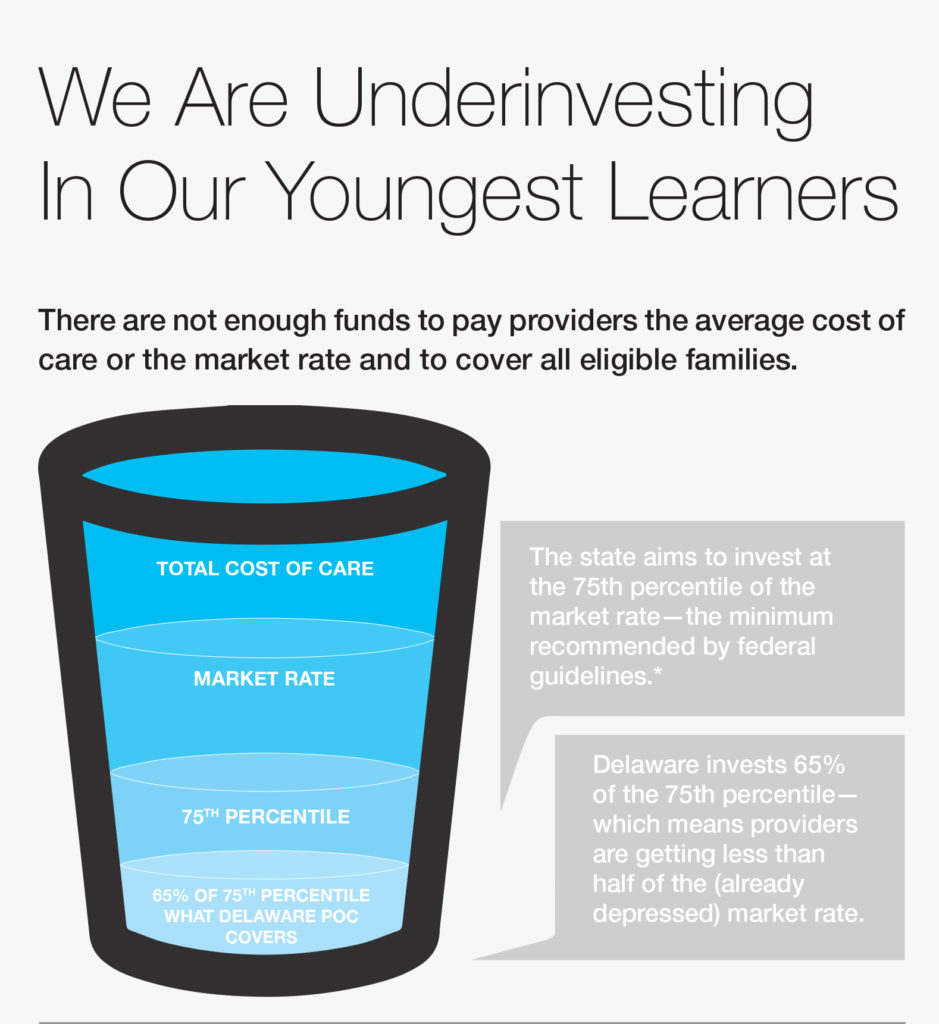

- A drop in enrollment could impact public school funding for future years. This dip in enrollment may also mean a dip in funding. In Delaware, state funding for schools is driven by a count of student attendance in the fall, typically around September 30 each year. The state then uses this count to fund schools for the following school year. Therefore, this year’s decrease in numbers could mean less money for districts to work with for all students. For example, if students who left public schools this year, or families who deferred public kindergarten for a year return next year, schools might have less funding than they should for the number of students enrolled. Should this happen, schools could encounter capacity issues, staffing concerns, and face overcrowding in many of their classrooms, especially kindergarten classrooms.

As the News Journal reports, the typical safety net for Delaware districts is the estimated count of student enrollment that districts take each spring. This is an estimate of student enrollment for the next school year, and the state is required, by Delaware code, to fund 98 percent of the students counted. During a Joint Finance Committee meeting in February, Secretary Bunting mentioned a potential proposal of a modified estimated unit count for this spring to address some of the funding concerns mentioned above.