*Photos by Jennifer Corbett and Cory Hafer.

For the students inside Cory Hafer’s classroom, such questions can launch an investigative journey and a love of learning. Hafer, a science and engineering teacher at Middletown High School, is Delaware’s 2024 Teacher of the Year. Over the course of five years at Middletown, Hafer has worked to cultivate an approach centered around curiosity and student agency–often giving them the keys and structure to lead their own learning.

Rodel caught up with the University of Michigan product to learn more.

. . .

Tell us a bit about your Teacher of the Year honor.

I was nominated by students at this point last February (our district puts out a survey to students, teachers, and the community). From there, our building held interviews and selected me as Building TOY. I then submitted an application for District TOY and went through interviews and formal observations and was selected in May as the District TOY. There was another round of applications for the State TOY process.

I met the other 19 candidates in our district, and thought, there’s no way district could happen, right? Then I got district and I was like, there’s no way state could happen. The whole thing has felt very surreal. It was totally off my radar. I kind of found myself thrown into this spotlight without being prepared for the spotlight.

It’s been weird, but I’m excited and I’m getting to the point now where I’m used to having a microphone and sharing what I’ve learned over 12 years of teaching with other people. I’m embracing it now.

How have you been able to build a classroom culture that is welcoming and inclusive?

It’s been one of those things that has been intentional my whole career. You learn early that students are innately curious about the world. And part of my education at Columbia was talking about and learning: basically don’t kill the wonder in school and particularly in science.

When you have kids asking you: is there a difference between happy tears and sad tears? Well, I don’t know. Let’s look that up. And it turns out they are actually chemically different. I want my classroom to be a space that’s interesting for students and I want to tap into that curiosity.

Then I realized as I got better at classroom management, even if I taught a really good lesson, maybe it didn’t work for everybody. How do I reach that kid who has his head down? You start to realize that nobody can learn if they’re not in the right mindset.

How important is cultivating a sense of curiosity with students? Especially when it comes to science?

With any learning, even when it comes to English and world history and math, there’s so much cool stuff there.

If I just tell you a bunch of stuff, it’s not going to stick, but if you’re grappling with it, and you’re fitting what you learn now with what you had learned, you retain it better. And experiences that don’t quite fit force you to change your schema. I think that exploration and that nonlinear journey are really important to follow in classes.

We’ve seen headlines over the last few years about teacher shortages and burnout. How are you seeing that play out?

I know my classroom space and I know I can talk about my experience and what works for me. But I am passionate about education. I love what I do. I invest a lot of time in it. And burnout’s a real thing. How do I manage it? How do I keep it sustainable? Because it’s easy to get sucked into it and just want to do more.

Part of one strategy that’s worked for me and would be good to remind young teachers: You don’t have to be perfect. It is totally fine to make mistakes. You’re going to fail miserably sometimes.

And as long as you’re reflecting on that and trying to avoid it in the future, you can’t look back. That’s probably the number one thing, don’t try to be perfect.

And then also, don’t be afraid to say no. Like, when you, if you get to the point where you’re like, I am so stressed and I’m having a mental breakdown, well, that’s not going to be good for anyone. So you have to find ways to dial back planning or say no to the things that aren’t absolutely essential to be there for students the next day.

As a profession, potentially building in counseling or like mental health days where that’s actually encouraged could be a healthy option.

Our administration at Middletown in particular is just so supportive. So knowing that you have those people in your corner is huge.

Being Teacher of the Year comes with a lot of opportunities to speak and engage with lawmakers and state leaders. What messages will you try to get across in those situations?

My first big speech that I’m actually really excited about is going to be to the Educators Rising State Conference that’ll be at University of Delaware on February 21-22.

I’ve been thinking a lot about that. And one of the things there is I want to highlight is why teaching is so rewarding.

I’ve been reflecting a lot about how if we didn’t have teachers and public education, our world would be a pretty terrible place. And so it’s kind of cool to think about how many people show up every day to make sure that kids learn so that our future can be bright. It’s wild.

I’ve also been shifting grading a lot and I’ve been doing project-based learning for the last five years.

We’re trying to answer a question in a lab rather than do a cookie cutter lab. You want to know why pineapple won’t let gelatin set. Well, let’s develop an experiment to figure that out. And five different groups get five different answers. And then we kind of debate what’s going on.

With projects like that, it becomes really hard to grade. Maybe your experiment failed, but it was a cool process and experiment. So are we grading on the concept, the final product, the process? I think project based learning is where we need to go in all disciplines because it’s more learner-centered and engaging.

So that’s an area I think I want to develop over the next year. And honestly, probably the rest of my career is, how in the world do we assess so that students can learn? And then how do we scale it?

I wrapped up this week with the semester. I did grading conferences with all my students. It was very time intensive, but it was amazing. For the first time in 12 years, I have not had a single student say, how do I get this 91 to a 94? They were like, yep, 91. I agree with that.

There’s no grade bickering and it’s awesome. I feel energized about that. Especially knowing that students are talking about their learning and setting future goals, even at the end of the course.

Now you’ve been part of the Middletown Community for five years. What makes it such a great fit for you?

The interesting thing at four of the districts I’ve been in: students are students. They have similar learning needs, diverse interests, and are curious.

Families seem to be pretty engaged in our school. A big thing that sets Middletown apart is it has the strongest sense of culture that I’ve seen in a school. My wife kind of makes fun of me for having so much Middletown gear, you know, because I have like five or six sweatshirts and all these t-shirts.

And I think stuff like that, as silly as it seems, helps build community. You know, we’ll have a Cavs Friday or like on Tuesday, we wear our unified Special Olympics shirts. So it feels like a very cohesive family, even across schools in the district.

And that’s a big determining factor for teachers sticking around, right? Having strong leadership in place that the teachers feel confident in and who have their backs?

Definitely. And there are two other things that do jump out. One is professional development opportunities, which have just been unreal compared to what I was used to in other districts.

There is a lot more encouragement, like, join this book study and we’ll pay for your book. There are lots of opportunities like that. And, then there’s really good funding to support teachers, which has resulted in supporting 1:1 technology, strong music programs, work-based learning opportunities, etc.

And fingers crossed on the Appoquinimink referendum passing on April 23rd because that will present challenges for the district if it does not. I think it is important for the community to understand how vital education is to our local community and overall to the world. Our district has experienced huge growth that is projected to continue. To support a growing population and ensure equitable pay for educators, it will be necessary to invest.

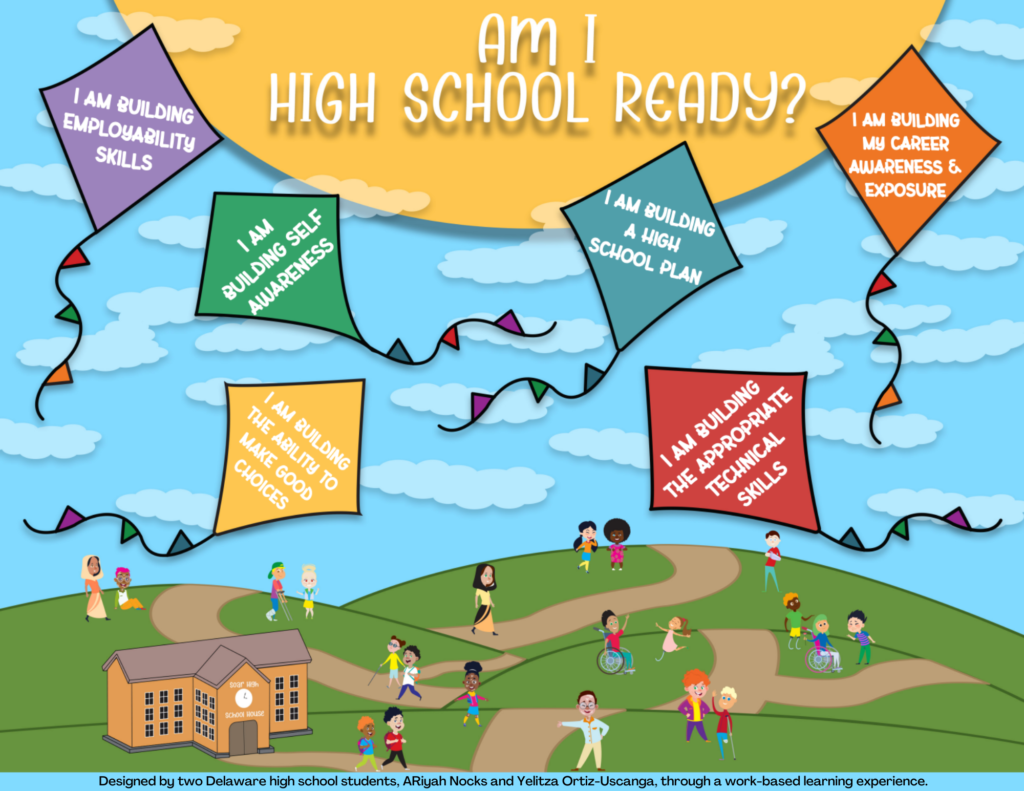

How have you helped bolster work-based learning opportunities at Middletown?

Work-based learning and career pathways have been really powerful at Middletown. In my engineering pathway, a lot of our students go on to be engineers, but a lot of them realize, hey, I don’t actually love engineering. I actually think I want construction instead, or a trade. It gives a relevance to our learning in a way that makes a huge difference.

The CTE coordinators have been phenomenal at helping connect us with industry partners. It’s to the point now where if I’m looking for a professional to come in and do a guest speaking event, or to mentor a group, that list of people is like 60-plus long.

And I would love to expand it because I think that’s where we can get those real-world opportunities, not just learning about stuff in the textbook, but solving a problem that exists.