Celebrating Superstars

Last week, The Partnership, Inc. (an affiliate of the Delaware State Chamber of Commerce), celebrated another sterling entry in its long-running Superstars in Education awards program.

Superstars is a statewide awards program that seeks to promote and share programs and best practices in education that show measurable results and raise student achievement. The awards typically go to local educators who have implemented and sustained a creative, unique program, or a teaching practice that works to raise student achievement.

The Rodel Foundation was front and center in this year’s program. Rodel’s president and CEO Paul Herdman serves on The Partnership’s Board of Directors, Rodel program officer Jenna Bucsak served on this year’s selection committee, and senior communications officer Matt Amis contributed written profiles of two award-winning programs. Rodel also sponsored the inaugural John H. Taylor, Jr. Leadership in Education Award, which went to Wilmington University president Jack Varsalona.

Scroll below for Matt’s articles, and read this month’s issue of Delaware Business magazine to learn about the rest of the 2016 Superstars in Education.

(Republished with permission from the DSCC. Photos by Tom Nutter.)

“Keys to Success”

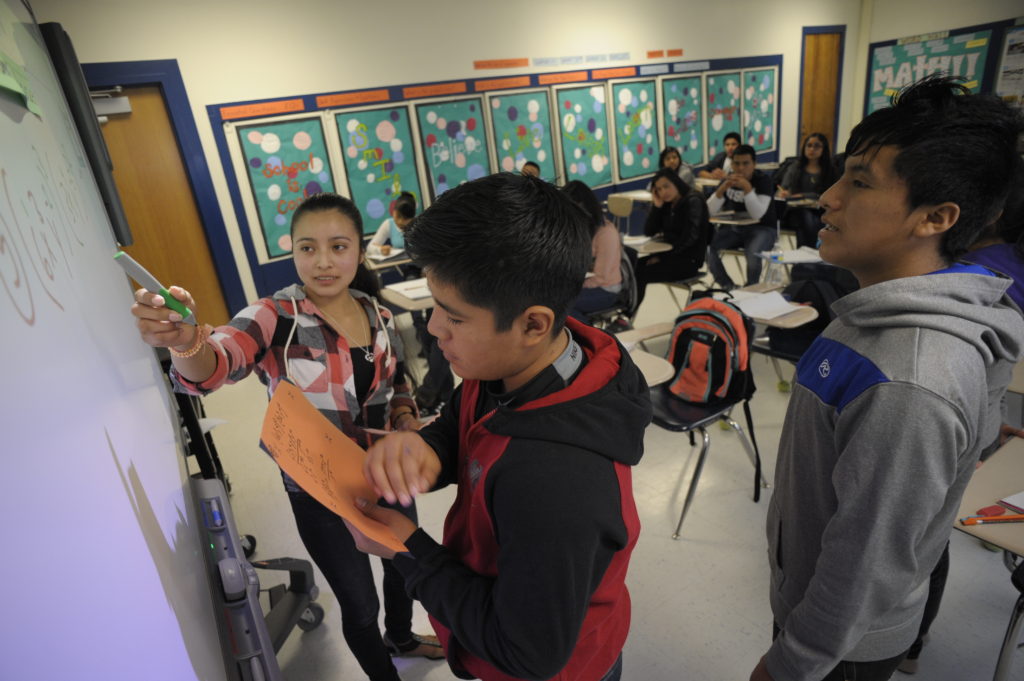

A.P.E.L.L. Program, Indian River School District

In July of 2014, Governor Jack Markell caused waves when he announced that Delaware had accepted 117 children who illegally immigrated alone into the U.S. In a letter, he called the U.S. a “nation of immigrants,” saying “the humanitarian crisis of unaccompanied minors fleeing dangerous situations at home does not just affect our border states; it impacts all of us as Americans. Whatever one’s politics, we are a nation of immigrants.”

A large portion of those children were high school aged boys, who fled abject poverty and violent crime in the Central American nation of Guatemala. Many cited friends or relatives living in Western Sussex County—particularly places like Georgetown, where large swaths of migrant laborers work in poultry plants and on farms.

Many of the teenagers also came to Delaware to work. Only most were too young to legally find employment. Instead they were told they needed to attend school.

Enter the Indian River School District and the Accelerating Preliterate English Language Learners (APELL) program. From the Carver Center in Frankfort, Dr. LouAnn Hudson and a team of personnel work intensely with newly arrived English Language Learner students who have had major interruptions in their schooling. The wave of Guatemalan students in 2013-14 is a perfect example of the type of students the program serves, but it’s not the only example. Immigrant students from Mexico, Haiti, and Turkey have also been enrolled in APELL.

“What makes this program truly unique is that the need is very great,” Hudson says. “Many of these kids are unaccompanied youth who have travelled thousands of miles. Many of us can’t even imagine that journey, and what they’ve been through to come to this country.”

While each APELL student is different, many come from impoverished backgrounds with very little formal education. And while Spanish is the official language of Guatemala, very few APELL students can speak or read it—having been raised on rural, regional dialects like Mam, which is rooted in Mayan tradition. Getting these students up to speed in Spanish—let alone English—is an enormous challenge. “The transition is that much harder for them,” Hudson says. “We’re not just transferring skills in one language, but trying to build literacy, language skills in any language.”

To get there, APELL staff spend half the day with its students at the Carver Center, where they undergo sheltered instruction in English language arts, direct English language instruction, reading intervention and mathematics. The staff also incorporates “new student orientation” facets into lessons, like American culture and general school community guidelines. The students then spend the afternoon at their regular high school, where they receive typical elective and academic ELL classes.

APELL, along with myriad community partners and the yeoman work of Parent and Community Liaison Diaz Bonville, secure wraparound services for students, ranging from medical, dental, vision and mental health supports, as well as nutritious food, clothing, and school supplies.

“Our reality with these students is—once they are here, our community has been very generous,” Hudson says. “And we know that they can be more successful in this country with an education. So we preach to this idea of graduating from high school.”

Just two years old, the program has yet to graduate its first class. Yet it continues to flourish. Enrollment has grown from 40 students to 90, and 26 students have recently returned to full-time courses at their home high schools. Testing data on the “measure B” Visions assessment, which measures speaking and listening, has also grown exponentially among APELL students. Anecdotally, many students have expressed a desire to continue their education.

“I think they are motivated to learn,” Hudson says. “They want to speak the language. A lot of them might not have immigrated with families or with parents, but many of them have strong connections to this place and the people they’re living with.”

“Exploring Mother Nature”

Outdoor Classroom, Postlethwait Middle School

When Todd Klawinski imagines the view from his classroom window, it is filled with vibrant colors.

Klawinski, who teachers seventh and eighth grade science at Postlethwait Middle School in Camden, is the brains behind the Outdoor Classroom—a repurposed drainage pond that will soon serve the entire Caesar Rodney School District as a miniature nature preserve.

Established in 2010, the Outdoor Classroom is a multipurpose, cross-curricular learning space. While it’s still a work in progress, when complete, it will serve 850 students at Postlethwait and 75 staffers.

The area, which contains a meadow, forest, and pond habitat—is meant to promote stewardship of nature and a sense of community responsibility, while immersing students in meaningful outdoor experiences, which studies show can improve health, academic success, and behavioral development.

“The 3-D world of the outdoors cannot be repeated indoors,” says Klawinski, who has a background in botany. “Kids have got to get outside to see how the water flows between some rocks, or how the wind blows through the grass. They have to get bit by a mosquito, get dirty on the ground, climbing a tree. It’s immersion education.”

The Outdoor Classroom got its start five years ago. Klawinski was in his classroom in the midst of a conversation with his principal. The science teacher glanced out the window when inspiration struck. “I looked out the window of my school, looking at this drainage ditch. I said, ‘Can I have that?’ I can’t just look at the waste site as a waste. Let’s utilize everything at our hands as a resource.”

Where the school and its neighbors saw a storm water management pond, Klawinski saw possibilities. He began mobilizing students, volunteers, and community members to expand, clean up, and begin planting native plant species around the classroom. This spring he hopes to complete a 30-by-14-foot deck that will overlook the property.

Overall, the space—roughly 40 yards wide and 50 yards long will see pin oak and cedar trees grow, while chinaberry, Japanese honeysuckles, and milkweed bloom. With flora will come fauna, like bullfrogs, ducks, foxes and praying mantises. “All native to the region and some to just Delaware,” Klawinski says. A community garden is also in the works.

This past school year, students at Postlethwait utilized the Outdoor Classroom in an exploratory sense, Klawinski says. He’ll let students loose on the space to explore with butterfly nets or to flip over logs in search of bugs. “Let them restore their ability to explore and connect with nature.” But if the teacher has his way, the experience—and the concept—will continue to blossom. At Postlethwait, the Outdoor Classroom will link with Next Generation Science Standards to bolster classes like Diversity of Life, Ecosystems, and Weather. Since the Outdoor Classroom’s inception, eighth grade science scores on standardized tests have spiked from 56 percent proficient in 2010-11, to 68 percent proficient in 2014-15.

In its next phase, the Outdoor Classroom would have new partners in local agencies and partners like DNREC, and scale to the other schools in the district. While it’s rooted in science lessons, the Outdoor Classroom could eventually make a natural setting for poetry lessons, as well as physical education or the arts.

Much like the patch of land itself, the ideas and inspiration behind the Outdoor Classroom continue to bloom.