Treating the Cause, Not the Symptoms: What Education Can Learn from the Social Determinants of Health

Individual behaviors play a role in educational outcomes, but inequitable social and economic factors loom even larger.

We know that children of all backgrounds—including those from adverse environments—can find success in school and in life. But the stark, empirical reality tells us public education still mostly favors the haves over the have-nots. Research shows (see also here and here) that access to three main levers of money, resources, and power still by and large determines whether a child will get a good education.

There is little doubt among education reformers that this needs to change. But after decades of efforts and initiatives aimed at closing achievement and opportunity gaps, the scales remain mostly unbalanced.

As we in the education world chip away on important issues like career preparation, 3rd grade literacy, or social and emotional learning, one can argue that the bigger, more important battles are the ones that influence broader federal, state, and local government policies that direct the all-important flow and distribution of money, power, and resources.

From finance to justice to social policies—there are many examples of indirect levers that can have strong impacts on students and their families, including property tax distribution and payday loan laws. Data shows persistent academic disparities related to income: Impoverished students are not inherently less smart, they are just less likely to have access to high-quality early childhood programs, adequate health care, and reliable transportation—things we know sets kids up for success in school.

Like the fabled Butterfly Effect, there are many seemingly unrelated forces, factors, and decisions that impact equity and our public education system.

Often, those of us working in education policy direct our focus at the individual-, school- or program-level, without addressing the role inequitable policy plays in education outcomes. While effective programs can provide students, parents, and teachers with supports they need in the here and now, they often don’t address the root of educations problems.

For example, parent engagement programs are well-intentioned attempts at getting parents more involved with their child’s academics. Research on parent involvement found that many programs start with the assumption that some parents do not care about their child’s education. However, these programs don’t always address the barriers to involvement that parents face, including long work hours, lack of childcare, lack of transportation, language and cultural barriers, and exclusive school policies.

Noble as they are, such programs often face an uphill battle when they try to change individual behaviors rather than advocating for transformative policies.

But what if we borrowed a page from the health reform playbook?

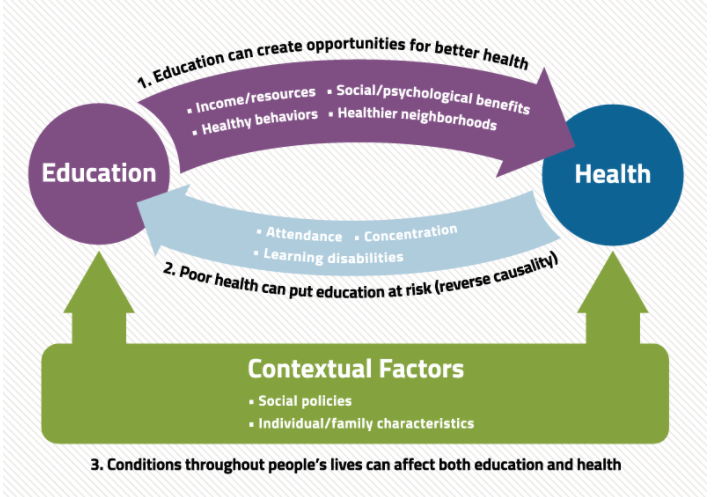

The social determinants of health is an approach that shifts the framing of health reform debate from the individual to the system. This approach takes a holistic view by examining the interconnectedness of education, health, and social factors such as policymaking. And it does represent an innovative approach to dealing with our public health woes—and poses a ripe opportunity for education reform.

The Social Determinants of Health

Next month at the 10th Annual Vision Coalition Conference on Education, leaders from Delaware’s health, education, public policy, and social services worlds will collide on stage for a panel discussion on the social determinants of health and education.

So what exactly are the determinants of health? Public policies, income, individual behaviors, social power, public safety, and discrimination to name a few. Social and economic factors, at around 40 percent, are the largest contributors to a person’s health, according to the National Association of Community Health Centers—compared to health behaviors (30 percent), physical environment (10 percent) and clinical care (20 percent).

Health care reformers use this idea to illuminate the role that money, power, and resources play in health access and outcomes. And, education and health are certainly interdependent (here and here). Typically, Americans with more education live longer, healthier lives—while poor health can compromise good education if a student cannot focus, is missing school, or has a learning disability.

Education reform could do well to learn from this example and begin to focus less on changing individuals and more on creating and implementing transformative, equitable policies.

Data tell us vast gaps exist between students of color and those from low-income backgrounds when compared to their white, more affluent peers. While we cannot discount the role individual behavior plays in educational outcomes, we must pay explicit attention to how policies and practices influence behaviors and outcomes.

Changing the narrative shifts the approach

By examining the problem from the lens of policy and practice, reformers can begin to ask hard questions about their efforts: Does our work target rules, practices, and norms that create, maintain, and exacerbate inequitable education disparities and outcomes?

Economic and social policy greatly influence how students perform, the efficacy of teaching practices, and the role of parents in education. As education reformers recognize this, they will begin to scrutinize the distribution of money, power, and resources and form solutions that create a fairer balance of these factors.

The social determinants of health offers an innovative approach to education reform that requires us all to ask hard questions about how we select the point of change, what (or who) we see as needing to be changed, and how we intend to change it. As we continue to search for solutions, we have an opportunity to use this approach to holistically address the root source of inequitable educational outcomes, and hopefully, to create a sustainable education system that equitably serves all students, teachers, and parents.