We Shouldn’t Depend on Market Rate Studies to Fund Early Learning

The child care industry across the nation is in dire peril. In Delaware, the situation is just as grim. Advocates are rallying around the state’s budgetary process in hopes of increasing state investments to save struggling providers.

Even before COVID-19—which caused havoc by raising costs while lowering enrollment—early child care centers were in a financial predicament.

It’s because Delaware invests less than 25 cents for every dollar per child in children ages birth-5 compared to the state investment in children in K-12—yet brain development is greatest before kindergarten. Purchase of Care (POC) is a state subsidy for child care that helps low-income parents who work, are enrolled in training or school, or have a medical need. But POC rates have been extremely low and don’t cover the actual cost of care.

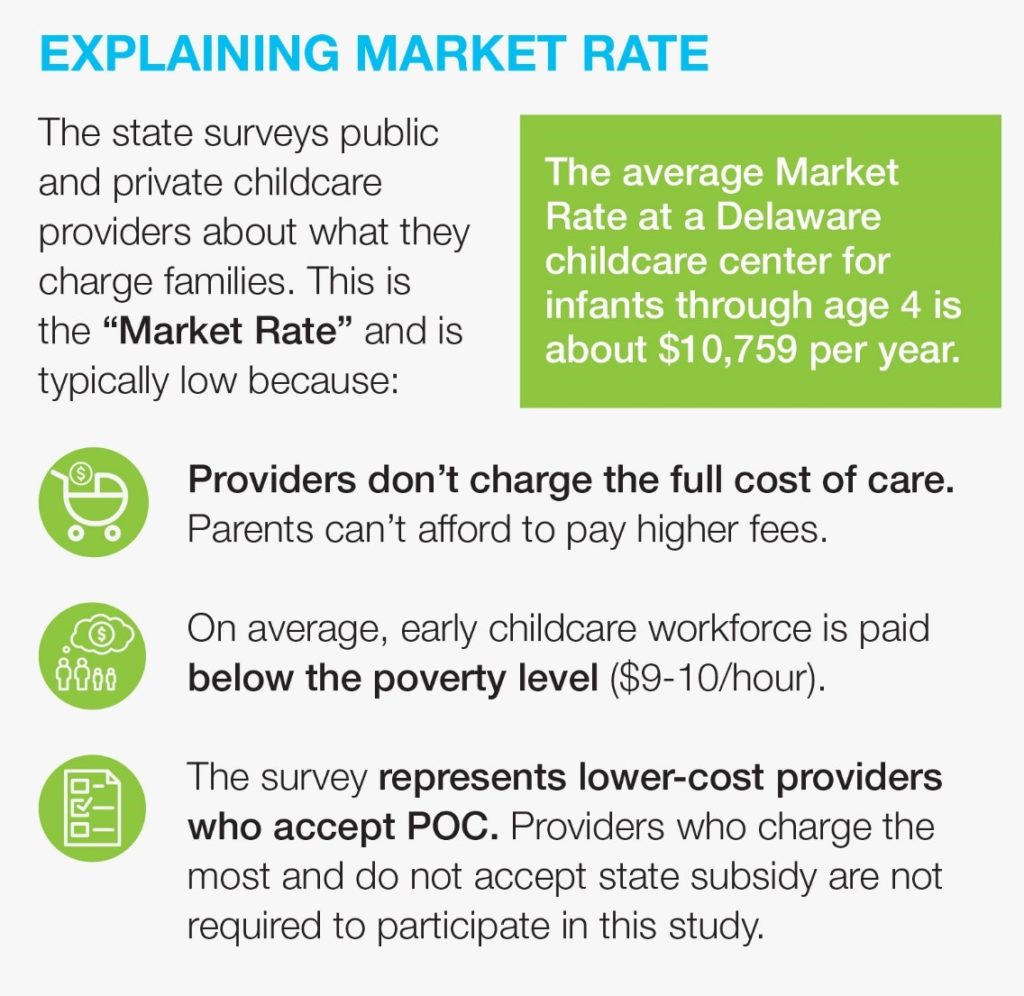

One reason the POC process isn’t ideal is that it gleans its presumed costs from a flawed “market rate study” process.

Although the state was required to release a market rate study representing all child care providers’ rates, there have been challenges in accuracy and response rates. Here are just a few more reasons why they’re not ideal.

- Market rate surveys are based on a market that is broken.

- Higher-quality care costs more than most families can afford, which lowers demand for quality.

- The market encourages price competition. This leads to lower prices (tuition fees) which discourages investment in quality care.

- Market rate surveys only report on prices charged, which can be different from the true cost.

- Prices that child care programs charge families care are significantly lower than the estimated true cost of providing basic care and high-quality care.

- Some prices don’t reflect other contributors to true cost, such as churches or nonprofits who loan space for free or discounted rates.

- In low-income areas, providers receive a low subsidy rate and the price (what providers charge) must be set low, but the cost (expenses) of providing quality care is still high.

- In Delaware, the cost of infant care is approximately 64 percent higher for an infant compared to a four-year-old. The subsidy pays only eight percent more for an infant than a four-year-old.

- Market rate surveys do not capture all forms of child care.

- Market rate surveys do not include informal arrangements outside of the typical market.

- In places where child care deserts exist (typically in rural and low-income areas), or where families need to find specialized care for various reasons, many families find alternative ways to find care for their child, such as relying on friends and family.

- Some families may not pay for informal arrangements, but many do. For arrangements where families do pay, they are not likely to be included in a market rate survey.

- And, a number of child care providers do not respond to the survey—including private and public schools, which are exempt from child care licensing requirements, and for profit child care centers who do not take state subsidy and are therefore disincentivized from completing the survey.

Market rate surveys use current rates to set future reimbursement rates.

-

- States are required to revisit their market rate every three years, but a lot can change in three years that could influence the price (what child care providers charge families) and cost (providers’ expenses) of care. The COVID-19 pandemic is a perfect example of this. According to the Bipartisan Policy Center, components (expenses) that drive the cost of providing child care: rent and utilities, materials and administration, food, personnel (salaries and benefits).

- And, even independent of COVID-19, costs go up about two percent per year.

So what should Delaware do?

- Increase child care subsidy rates to enable families to access 75 percent of child care providers, based on the 75th percentile of the market. We estimate this will cost $40 million in FY22.

- And, to stabilize families and providers, child care should be paid based on the enrollment, not attendance of a center, which is estimated to cost $20 million in FY22.

- In Delaware’s 2022-24 Child Care Development Fund Plan, which will be submitted to the federal Administration for Children and Families, Delaware should adopt the cost of quality care cost methodology adopted by Washington, D.C. and other states.

Related Topics: delaware purchase of care, delaware schools, early child care, early child care funding, early learning, market rate study, purchase of care