Governor John Carney recommended significant increases in his FY24 Budget: over $10 million to increase child care rates, family eligibility, pre-K, and for children with special needs. These initial steps will continue to stabilize the foundation and support children and families for the high-quality system we aspire to long-term.

Although the governor’s budget outlines strong initial steps to stabilize child care so they can begin to serve more families, there are significant challenges that will require long-term commitments:

- Workforce. According to a Early Learning Needs Assessment by the Delaware Office of Early Learning, the early learning workforce has decreased by 12.6 percent in the last five years. Fifty-eight percent of programs reported that their inability to hire and retain staff was the primary reason for classroom closures, and 53 percent reported at least one classroom closed. The consensus has been that low wages and lack of benefits continue to be the biggest barrier to hiring staff.

- Cost for Families: In a recent survey of hundreds of parents and caregivers, 50 percent said child care is their biggest monthly expense, with a majority, 81 percent, said child care expenses are holding their family back from improving their situation in at least one way, including taking a job or increasing hours at work, going back to school, or buying a home. In a recent fact sheet highlighting affordability, data show that child care, per child, costs 20 percent of the median income in Delaware. Even those who qualify for public assistance can expect to pay 10 percent of their family income on care.

“Our experience with finding child care has been a series of epic failures. We were put on numerous waitlists for centers in our area—most with a year-plus waiting list and insanely expensive.” -Delaware parent

- Access to Publicly Funded Care: Access has decreased to only one in seven children served through public funding, which means 85 percent of children do not have access to public early care and education —and children are only young once. They need and deserve access to formal care and education so they can engage in critical early learning developmental opportunities. And, this access has decreased in recent years despite funding remaining stable.

- Availability of Care: If they can afford care, long waiting lists continue to plague caregivers seeking child care, with more pronounced challenges in Kent and Sussex counties. Among caregiver respondents, 71 percent looked into two or more options for their child—and more than a third (37 percent) were placed on a waitlist. child care, compared to 16 percent of children in New Castle County. A recent fact sheet on child care accessibility noted that waiting lists are as high as 1,500 families and years long in some cases.

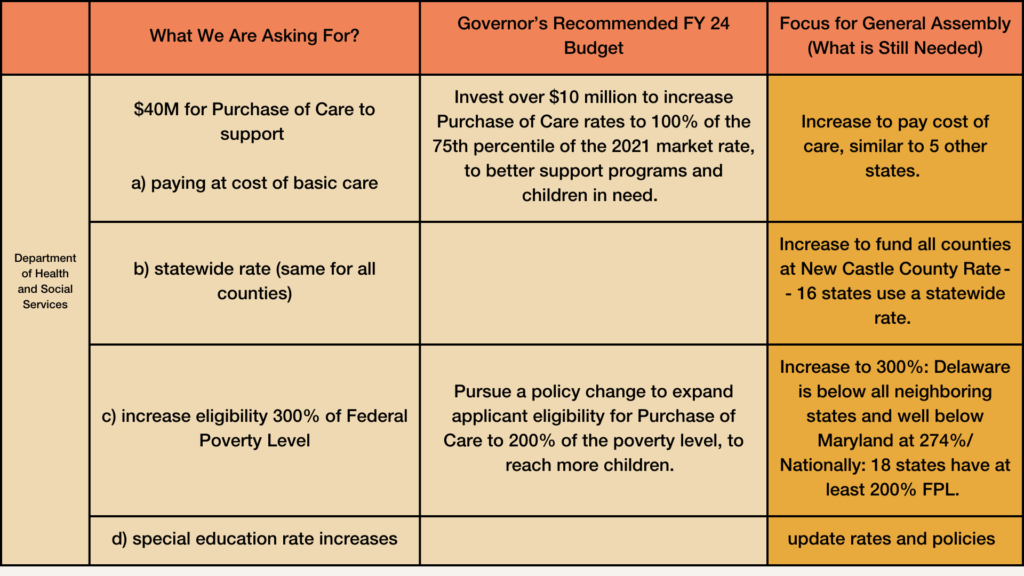

- Advocates have outlined areas where the General Assembly—especially the Joint Finance Committee—can build on the Governor’s Budget to address these issues for families and children.

Contact members of the Joint Finance Committee to ask them to build on the governor’s budget here or here.

- Federal Preschool Development Grant ($8 million/year for three years)

- More state-funded preschool seats (ECAP) including infants and toddlers

- Pilot of universal Family Connects Home Visiting Model

- Improved Child Care Resource and Referral for Families

- Workforce supports for professionals including pathways, coaching

- Quality Improvement System

- Early Educator Bonus Program reopening February

- Lt. Governor Bethany Hall-Long’s Press Conference on Early Childhood (Advisory Committee Report)

These efforts have demonstrated strong collaboration and alignment with the Delaware Early Childhood Council Strategic Plan.